A Commercial Lease Agreement is a legally binding contract between a landlord and a business tenant for the rental of commercial property. Unlike residential leases, these agreements are more complex and negotiable, tailored to meet the specific needs of a business. Business owners must understand that commercial leases often come with longer terms, higher financial commitments, and limited legal protections compared to residential leases, making it crucial to review every clause carefully before signing.

One of the most important sections to pay attention to is the rent and operating expenses clause. This not only outlines the base rent but may also include additional costs like property taxes, maintenance, insurance, and common area charges (known as CAM fees). Depending on the lease type—gross, net, or triple net—the tenant might be responsible for a significant portion of the building’s upkeep. Clear understanding of these terms can prevent unexpected expenses and disputes down the line.

Other key clauses include the use clause, which defines how the tenant may use the property, and the termination or exit clause, which outlines conditions under which either party can end the lease early. Business owners should also look for clauses related to renewal options, rent increases, and property modifications. Consulting with a commercial real estate lawyer before signing is highly recommended to ensure the lease aligns with the business’s goals and protects its long-term interests.

Why Commercial Leases Are a Different Beast (Residential vs. Commercial)

First things first: mentally set aside almost everything you assume based on typical apartment leases. The legal and practical landscape for commercial leasing in the U.S. operates under fundamentally different assumptions and rules:

Fewer Consumer Protections:

Residential landlord-tenant law across the U.S. is often heavily influenced by state statutes designed to protect individual tenants, who are generally perceived as having less bargaining power and sophistication compared to landlords.

These laws often imply warranties (like the warranty of habitability) and dictate specific procedures for things like security deposits and evictions. Commercial leases, however, operate largely under contract law principles, assuming that the parties involved (landlord and business tenant) are more sophisticated entities capable of negotiating terms on a more equal footing (even if this assumption doesn’t always reflect the reality, especially for small businesses).

Consequently, there are far fewer built-in statutory protections automatically afforded to commercial tenants. What you negotiate into the lease document is paramount.

Extreme Negotiability (In Theory):

Reflecting the assumption of sophisticated parties, almost every single clause in a commercial lease is potentially negotiable – the base rent, the length of the term, rent escalation formulas, responsibility for repairs and maintenance, signage rights, renewal options, operating expense pass-throughs, guarantees, and much more.

Landlords will typically present their standard lease form, often drafted by their attorneys to be very landlord-favorable, but it should almost always be viewed as a starting point for negotiation, not a take-it-or-leave-it proposition.

Your ability to negotiate successfully hinges heavily on factors like prevailing market conditions (is it a landlord’s or tenant’s market?), your desirability as a tenant (your creditworthiness, business track record, the prestige of your brand), the specific property, and, crucially, your level of preparation and representation.

Inherent Complexity and Length:

These agreements are invariably significantly longer, more detailed, and more complex than residential leases. They must address a wide array of business-specific issues that simply don’t arise in a residential context.

This includes precise definitions of the permitted business use (and restrictions on other uses), intricate formulas for calculating and allocating shared operating expenses (Common Area Maintenance or CAM), detailed rules regarding alterations or improvements needed for the tenant’s specific business operations (tenant build-outs), restrictions on signage, allocation of responsibilities for compliance with laws (like the Americans with Disabilities Act – ADA), environmental indemnities, and complex clauses dealing with subordination and lender requirements.

Significant Financial Stakes and Long-Term Commitment:

Commercial leases typically involve much larger sums of money – both in terms of monthly rent and potential additional costs – compared to residential leases. Furthermore, the commitment periods are usually much longer, with terms of 3, 5, 7, 10 years, or even more being commonplace.

The financial health and operational success of your business can be directly and profoundly tied to the terms negotiated (or not negotiated) in its lease agreement.

While the context differs greatly, the fundamental concept of exchanging rent for the right to use property remains. If lease agreements are entirely new territory, reviewing the basics in What Is a Lease Agreement? A Beginner’s Guide can provide a useful conceptual foundation before diving into the unique complexities of the commercial world.

Decoding Common Types of U.S. Commercial Leases: Understanding Your Cost Structure

Before you even begin dissecting individual clauses, it’s essential to understand the basic structural type of lease being offered. This is critical because the lease type dictates the fundamental approach to allocating the property’s operating expenses between the landlord and the tenant.

This allocation is a major factor in determining your true total occupancy cost, which goes far beyond just the base rent figure.

Gross Lease (or Full-Service Lease)

Think of this as the relatively all-inclusive option, conceptually similar to many residential leases in terms of cost structure. The tenant pays a single, flat base rent amount periodically (usually monthly). The landlord is responsible for paying most, if not all, of the property’s operating expenses directly. These expenses typically include property taxes, property insurance, and common area maintenance (CAM) costs (which encompass things like landscaping, security, cleaning and maintenance of shared hallways, lobbies, elevators, restrooms, parking lots, etc.), and sometimes even utilities and janitorial services for the tenant’s space.

- Pros for Tenant: Highly predictable monthly occupancy cost, making budgeting significantly easier. Less administrative burden as the landlord handles expense payments.

- Cons for Tenant: The base rent is usually considerably higher than in net leases because the landlord factors their estimated operating costs (plus a potential profit margin or buffer) into that flat rate. Tenants might indirectly pay for services they don’t heavily utilize or benefit from. There’s less transparency into the actual operating costs.

- Common Use: Frequently used for multi-tenant office buildings where allocating specific costs like utilities or janitorial per tenant can be complex.

Net Lease: Sharing the Operating Expense Burden

This is where the responsibility for operating expenses begins to shift towards the tenant, who pays these costs in addition to a base rent. There are three primary variations, distinguished by which specific expenses are passed through:

- Single Net Lease (N Lease): Relatively uncommon. The tenant pays the base rent plus their pro-rata share of the property taxes. The landlord remains responsible for paying the property insurance and all CAM costs.

- Double Net Lease (NN Lease): More common than single net. The tenant pays the base rent plus their pro-rata share of both property taxes and property insurance premiums. The landlord typically covers the costs of CAM and structural repairs (though CAM responsibilities can sometimes be negotiated).

- Triple Net Lease (NNN Lease): Arguably the most prevalent type of net lease, especially for single-tenant buildings, retail properties (like strip malls or standalone stores), and industrial/warehouse spaces. The tenant pays the base rent plus their pro-rata share (or the entirety, for a single-tenant building) of essentially all operating expenses: property taxes, property insurance, and all CAM costs. In a true NNN lease, the landlord effectively passes through almost all costs associated with owning and operating the property, except typically for structural repairs (like the roof or foundation, though even this can be negotiated).

- Pros for Tenant (Net Leases): The base rent is typically significantly lower than in a comparable gross lease, which can be attractive upfront. There’s potentially more transparency, as operating costs are often billed separately based on actual expenses (though careful review is essential).

- Cons for Tenant (Net Leases): Operating expenses can be unpredictable and fluctuate significantly from year to year, or even month to month. Property taxes can increase, insurance premiums can rise, and CAM costs (especially for things like snow removal, parking lot repairs, or HVAC maintenance in common areas) can spike unexpectedly. This makes budgeting much more challenging and potentially exposes the tenant to significant financial risk. Tenants must diligently scrutinize how these expenses are calculated, allocated (pro-rata share), and billed.

Modified Gross Lease (Hybrid Approach)

As the name suggests, this is a hybrid structure that falls somewhere between a Gross and a Net lease. The tenant pays a base rent, and the landlord and tenant specifically agree within the lease document to split certain operating expenses.

The exact division of responsibilities is entirely defined by the negotiation and the resulting lease language. For example, the lease might state the tenant pays base rent plus their own utilities and interior janitorial, while the landlord covers taxes, insurance, CAM, and structural repairs.

Or, it might include an “expense stop,” where the landlord pays operating expenses up to a certain amount per square foot per year (the “base year” amount), and the tenant pays any increases above that stop.

- Key: The specifics are entirely dependent on what is written in the lease. Read carefully!

Percentage Lease: Sharing in the Success (Retail Focus)

This lease type is predominantly found in the retail sector, particularly within shopping malls, lifestyle centers, or sometimes high-profile street retail locations. The tenant pays a fixed base rent (often lower than it might be otherwise) plus a percentage of their gross sales revenue generated from that specific leased location.

This percentage rent typically only kicks in after the tenant’s sales exceed a certain negotiated threshold amount, known as the “breakpoint.”

- Mechanism: The idea is that the landlord shares in the tenant’s success at that location, incentivizing the landlord to maintain a vibrant and attractive shopping environment that drives traffic. The breakpoint can be calculated in various ways (natural vs. artificial).

- Key Negotiation Points: The amount of the base rent, the exact percentage rate applied to sales above the breakpoint, the calculation method and level of the breakpoint itself, and, critically, the precise definition of “gross sales” (what specific revenue streams are included or excluded – e.g., online sales fulfilled from the store, lottery tickets, service fees) are all vital negotiation points.

Understanding the fundamental lease type being proposed is crucial because it dramatically affects your total monthly and annual occupancy costs. A seemingly low base rent on a NNN lease might initially look appealing, but if the property has high taxes or deferred maintenance leading to soaring CAM charges, it could ultimately prove far more expensive than a higher base rent on a Modified Gross lease where the landlord covers those volatile items.

Anatomy of a Commercial Lease: Critical Clauses to Scrutinize and Negotiate

Alright, let’s roll up our sleeves and get into the nitty-gritty details of the lease document itself. While every single clause in a commercial lease deserves careful reading and consideration (seriously, read it all, including the exhibits!), some clauses typically carry more weight, involve higher financial stakes, or are more frequently subject to negotiation than others.

Here are the ones that business owners absolutely need to understand, scrutinize, and potentially push back on:

The Premises Clause: Defining Your Space (More Than Just an Address)

This clause defines precisely what physical space you are renting. Ambiguity here can lead to major problems. It needs to be crystal clear:

Exact Description:

It must go beyond just the street address. It should clearly specify the suite number, floor level, or specific designated area within a larger building. Crucially, it almost always includes a statement of the rentable square footage (RSF) of the premises.

Pay extremely close attention to how this square footage is measured! Landlords often use measurement standards established by organizations like BOMA (Building Owners and Managers Association). These standards can sometimes include a share of common areas (like lobbies, hallways, restrooms) or even unusable space within the premises (like structural columns) in the calculation.

Since your base rent (often quoted as dollars per square foot) and your pro-rata share of operating expenses (in net leases) are usually based on this RSF figure, the measurement standard used can significantly impact your costs. Try to negotiate for a standard that measures only usable square footage (USF) or at least understand the implications of the standard being used.

Floor Plans/Exhibits:

Detailed, accurate floor plans showing the exact layout, dimensions, and boundaries of your leased premises should always be attached to the lease as exhibits and explicitly referenced within the Premises clause. Verify these plans match the actual space.

Common Areas:

The lease should clarify your rights and access to shared or common areas necessary for your business operations, such as hallways, restrooms, elevators, lobbies, loading docks, parking lots, and sidewalks. Are there specific rules or restrictions governing their use? Who is responsible for their maintenance (usually the landlord, paid via CAM)?

Parking:

If parking is included, the lease needs to specify the number of spaces allocated to you, whether they are reserved or unreserved, where they are located, any associated costs, and rules for employee and customer parking.

Expansion/Contraction Options:

Does the lease offer flexibility for future growth or downsizing? Look for clauses like:

-

- Right of First Offer (ROFO): Gives you the right to be the first party the landlord negotiates with if adjacent space becomes available.

- Right of First Refusal (ROFR): Gives you the right to match any bona fide offer the landlord receives from another party for adjacent space.

- Contraction Option: Allows you to give back a predetermined portion of your space under specific conditions (often involving a penalty).

- These options add valuable flexibility but need to be meticulously defined regarding timing, pricing, and procedures.

Lease Term & Renewal Options: How Long Are You Committed, and What Happens Next?

This section defines the duration of your legal commitment and outlines your options (if any) for extending your tenancy beyond the initial period.

Length (Term):

Commercial leases often involve substantial terms – 3, 5, 7, 10 years, or even longer are common, especially for retail or heavily customized spaces. Ensure the exact start date (Commencement Date) and end date (Expiration Date) are clearly and unambiguously stated.

Commencement Date vs. Rent Commencement Date:

Be aware that these might be two different dates! The Lease Commencement Date might be the official start of the lease term, perhaps when you gain access to the premises to begin any necessary construction or alterations (build-out). The Rent Commencement Date, however, might be later, marking the date you actually begin paying base rent.

This often follows a negotiated rent-free period (rent abatement) intended to cover your build-out phase. Clarify both dates.

Renewal Options:

The right to renew the lease is extremely valuable for a tenant, providing security and avoiding the cost and disruption of relocation. Landlords may or may not grant renewal options. If they are included, scrutinize the details:

Number and Length:

How many renewal options do you have (e.g., one 5-year option, two 3-year options)?

Rent Determination:

This is critical. How will the base rent be set for the renewal period(s)? Common methods include:

- A fixed dollar amount or fixed percentage increase specified in the lease.

- Adjustment based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or another inflation index (negotiate for a cap!).

- Set at “Fair Market Value” (FMV). If using FMV, the lease MUST clearly define the process for determining FMV if the parties can’t agree (e.g., an appraisal process involving one or three appraisers, defining criteria for comparability).

Notice Requirements:

What is the exact deadline and method for exercising the renewal option? It’s usually a specific window (e.g., no earlier than 12 months and no later than 6 months before the current term expires) and requires formal written notice. Missing the deadline almost always means forfeiting the renewal right!

Conditions:

Are there conditions attached to the renewal right (e.g., tenant must not be in default at the time of exercise or commencement of the renewal term)?

Rent: Base Rent, Escalations, and Additional Rent (The Full Cost Picture)

This section details all your monetary payment obligations under the lease.

Base Rent:

The fixed amount you pay periodically (usually monthly) for the right to occupy the premises. Ensure the amount and payment due date are clear.

Rent Escalations:

How and when does the base rent increase during the initial lease term? Landlords build in escalations to account for inflation and increasing property value. Understand the method:

Fixed Percentage Increases:

Common and predictable (e.g., base rent increases by 3% on each anniversary of the Rent Commencement Date).

CPI/Index Increases:

Rent adjusts based on changes in a specified inflation index. Try to negotiate a “cap” (maximum increase) and potentially a “floor” (minimum increase) to limit volatility.

Stepped Increases:

Predetermined flat dollar increases at specific points in the term (e.g., rent is $5,000/month for years 1-3, then $5,500/month for years 4-5).

Carefully model these escalations to understand your future rent obligations.

Additional Rent (Operating Expenses/CAM/Pass-throughs):

In Net and Modified Gross leases, this is often the most complex and contentious part of the rent structure. This covers your share of the property’s operating costs. Demand clarity and negotiate aggressively here:

CAM Definition:

Get an exhaustive list of what specific costs are included in Common Area Maintenance (or Operating Expenses). Landlords often use broad language. Push for specific exclusions. Common exclusions tenants should fight for include: capital expenditures (e.g., costs for replacing the roof, HVAC systems, repaving the parking lot – these should arguably be the landlord’s capital cost, not passed through as an operating expense, though amortization of capital improvements that reduce operating costs might be acceptable), landlord’s administrative fees (or negotiate a reasonable cap, e.g., 5-10% of total CAM), costs related to marketing the property or leasing other spaces, costs incurred due to the landlord’s negligence, costs specific to other tenants, interest on the landlord’s debt, depreciation, and costs of correcting initial construction defects.

Pro-Rata Share Calculation:

Understand exactly how your share of these expenses is calculated. It’s typically based on the ratio of your premises’ rentable square footage to the total rentable square footage of the building or center. Verify both figures.

Caps on Increases:

Try to negotiate annual caps on controllable operating expense increases (e.g., limiting increases to 5% per year over the previous year, excluding uncontrollable costs like taxes and insurance).

Audit Rights:

This is crucial. Insist on the right to audit the landlord’s books and records pertaining to operating expenses, usually once per year, at your expense (unless a significant error is found, then the landlord might pay). Landlords can make mistakes, or calculations can be opaque. Without audit rights, you have no way to verify the accuracy of potentially substantial charges.

Percentage Rent (Retail):

f applicable, ensure the breakpoint calculation, percentage rate, definition of gross sales, and reporting requirements are meticulously defined and fair.

Security Deposit & Guarantees: Landlord’s Safety Net, Your Financial Exposure

Landlords require security against potential tenant defaults or damages, but the form and extent of this security can significantly impact your finances.

Amount: Commercial security deposits are often significantly larger than residential ones, frequently equivalent to several months’ rent. The amount is highly negotiable based on your creditworthiness and business history.

Form: Can it be paid in cash, or is a Letter of Credit (LOC) acceptable or required? An LOC is a guarantee issued by your bank. Using an LOC can be advantageous as it doesn’t tie up your actual working capital in the landlord’s account, but banks charge fees for issuing and maintaining LOCs, and they often require you to collateralize the LOC with cash or other assets at the bank.

Interest: Unlike many residential leases, landlords are typically not required by law to pay interest on commercial security deposits.

Return Conditions: Clarify the conditions and timeline for the return of the deposit after the lease ends, accounting for potential deductions for damages beyond normal wear and tear or unpaid rent.

Personal Guarantee (The Big One): This is a critical point, especially for new or smaller businesses without a long, strong financial track record. Landlords frequently require the business owner(s) to personally guarantee the lease obligations. This means if your business entity (e.g., your LLC or corporation) fails and cannot meet its lease obligations (like paying rent), the landlord can legally pursue the guarantor’s personal assets – your house, personal savings, investments, etc. – to cover the debt.

Negotiation Strategy: Fight hard to avoid signing an unlimited personal guarantee. It puts your entire personal financial life at risk for your business’s lease. If the landlord insists on a guarantee due to the business’s perceived risk, try vigorously to limit its scope:

“Good Guy” Guarantee: Limits the guarantor’s liability to rent payments only up until the date the tenant vacates and returns the premises to the landlord (provided proper notice is given), rather than for the entire remaining lease term.

Cap the Amount: Limit the total dollar amount the guarantee covers (e.g., equivalent to 6 or 12 months’ rent).

Time Limitation/Burn-Off: Have the guarantee expire after a certain number of years if the tenant has remained in good standing, or have the guaranteed amount decrease over time.

Limit to Specific Individuals: If there are multiple owners, try to limit the guarantee to only certain individuals or cap each individual’s exposure.

Never sign a personal guarantee lightly. Fully understand the implications and explore all alternatives first. Get legal advice specifically on this point.

While the specific rules and amounts differ greatly from residential leases, understanding the basic concept of security deposits can be helpful. You can review fundamentals in Understanding Security Deposits in Lease Agreements, but always remember commercial practices are distinct and less regulated.

Use Clause: Defining What Your Business Can Actually Do in the Space

This clause specifies the permitted activities for your business within the leased premises. It might seem straightforward, but it can be surprisingly restrictive and impact your future flexibility.

Permitted Use: Landlords often want this to be very narrow and specific (e.g., “retail sale of women’s shoes and related accessories only”). Tenants should push for broader language (e.g., “general retail use” or “general office use”) to allow for potential evolution of the business, product line changes, or future subletting/assignment possibilities.

Exclusive Use Rights (Retail): Conversely, as a retail tenant, you might want to negotiate for an exclusive use clause. This would prohibit the landlord from leasing space in the same shopping center or building to another tenant whose primary business directly competes with yours (e.g., if you run a coffee shop, preventing the landlord from leasing to another coffee shop). Landlords are often reluctant to grant exclusives, but they can be very valuable.

Prohibited Uses: The clause will also list activities that are not allowed (e.g., anything illegal, uses generating excessive noise or odors, specific types of businesses restricted by zoning or other tenants’ exclusives).

Compliance with Laws: Ensure the permitted use complies with zoning regulations and other applicable laws.

Repairs and Maintenance: Who Fixes What?

This is a frequent source of disputes. The lease must clearly delineate responsibility for repairs and maintenance between the landlord and tenant.

Landlord’s Responsibilities: Typically include structural components of the building (roof, foundation, exterior walls), major building systems (like the main electrical service, plumbing mains, sometimes base building HVAC systems, elevators in office buildings), and maintenance of common areas (paid via CAM in net leases).

Tenant’s Responsibilities: Usually include non-structural interior maintenance within the premises (e.g., painting, light fixtures, interior doors), maintenance of systems exclusively serving the premises (like a dedicated HVAC unit, interior plumbing fixtures), and repairing any damage caused by the tenant or their invitees.

HVAC Systems: Responsibility for maintaining, repairing, and potentially replacing the Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system serving the premises is a major negotiation point. Landlords often try to push this onto the tenant, especially in NNN leases. Tenants should resist taking on replacement cost, or at least negotiate for the landlord to cover replacement if the system fails within a certain period or due to age/inherent defect. Capping the tenant’s annual maintenance cost is also a strategy.

Clarity is Key: Ambiguous language here leads to arguments. Define terms like “structural” and specify systems clearly.

Alterations and Improvements (Tenant Build-Outs): Modifying the Space

Most businesses need to modify the leased space to suit their specific operational needs. This clause governs that process.

- Landlord’s Consent: Landlords almost always require their prior written consent for any alterations, especially structural ones. Negotiate for consent not to be “unreasonably withheld, conditioned, or delayed,” particularly for non-structural changes.

- Process for Approval: Define the process for submitting plans and specifications for landlord review and approval.

- Who Pays? Typically, the tenant pays for their own alterations. Sometimes, landlords offer a Tenant Improvement Allowance (TIA) – a sum of money per square foot to help offset the tenant’s build-out costs. The amount and terms of the TIA are highly negotiable.

- Ownership of Improvements: Who owns the alterations at the end of the lease? Usually, anything permanently affixed becomes the landlord’s property.

- Restoration Obligation: Does the tenant have to remove their alterations and restore the premises to their original condition upon moving out? This can be very expensive. Try to limit this obligation, especially for standard improvements, or have it waived entirely.

Insurance and Indemnification: Managing Risk

These clauses deal with risk allocation and protection against liability.

Tenant’s Insurance: The lease will require the tenant to carry specific types of insurance, often including Commercial General Liability (CGL), Property Insurance (for tenant’s property and improvements), and potentially Workers’ Compensation and Plate Glass insurance. Pay close attention to the required coverage limits (often $1 million or $2 million per occurrence for CGL) and ensure your policy meets them. The landlord will typically require being named as an “additional insured” on the tenant’s CGL policy.

Landlord’s Insurance: The landlord will carry insurance on the building itself and their own liability, often paid for via operating expenses in net leases.

Waiver of Subrogation: Look for mutual waivers of subrogation. This means both parties’ insurance companies agree not to sue the other party to recover damages paid out on a claim, even if that party was negligent (e.g., if tenant negligence causes a fire damaging the building, the landlord’s insurer pays the landlord but cannot then sue the tenant). This prevents costly litigation between insurers.

Indemnification: This clause requires one party (usually the tenant) to defend and pay for losses or claims against the other party arising from specific events (e.g., tenant indemnifies landlord against claims arising from tenant’s operations within the premises). Ensure indemnification clauses are mutual where appropriate (landlord indemnifies tenant for claims arising from common areas or landlord’s negligence) and try to limit your indemnity obligations to claims arising from your negligence or willful misconduct, not just any event occurring on the premises.

Assignment and Subletting: Transferring Your Lease

What happens if your business needs change and you want to get out of the lease or let someone else use the space?

Landlord’s Consent Required: Virtually all commercial leases require the landlord’s prior written consent for the tenant to assign the lease (transfer the entire lease to a new tenant) or sublet the premises (lease part or all of the space to a subtenant while remaining liable on the original lease).

Standard for Consent: Negotiate for the lease to state that the landlord’s consent “shall not be unreasonably withheld, conditioned, or delayed.” Without this language, the landlord might have absolute discretion to refuse, even arbitrarily.

Permitted Transfers: Try to negotiate for certain transfers to be permitted without landlord consent, such as assignment to an affiliated company, a successor entity resulting from a merger or acquisition, or sometimes subletting a small portion of the space.

Landlord’s Recapture Rights/Profit Sharing: Landlords often include clauses allowing them to “recapture” the space (terminate your lease) if you request consent to assign or sublet, or demanding that you share any profit (rent received from the subtenant above your own rent) with them. Negotiate these terms carefully.

Default and Remedies: When Things Go Wrong

This critical section outlines what constitutes a breach of the lease by either party and what actions the non-breaching party can take.

- Tenant Defaults: Typically include failure to pay rent on time, failure to maintain the premises, violating the use clause, illegal activities, abandonment of the premises, or bankruptcy.

- Notice and Cure Periods: Negotiate for reasonable written notice from the landlord and an opportunity (a “cure period”) to fix the default before the landlord can exercise remedies (e.g., 10 days to cure monetary defaults like unpaid rent, 30 days for non-monetary defaults).

- Landlord’s Remedies: If the tenant defaults and fails to cure, the landlord’s remedies usually include terminating the lease, evicting the tenant, suing for unpaid back rent, and potentially suing for “accelerated rent” (the remaining rent due for the entire rest of the lease term, though this may be subject to the landlord’s duty to mitigate damages by re-renting).

- Landlord Defaults: The lease should also define landlord defaults (e.g., failure to make required repairs, breach of quiet enjoyment) and specify the tenant’s remedies (which might include suing for damages, rent abatement, or potentially lease termination for severe, uncured defaults).

Subordination, Non-Disturbance, and Attornment (SNDA): Protecting Your Tenancy from the Landlord’s Lender

This is a complex but important clause, especially relevant if the landlord has a mortgage on the property.

- Subordination: Your lease is typically subordinate (secondary) to the landlord’s mortgage. This means if the landlord defaults on their loan and the lender forecloses, the lender could potentially terminate your lease.

- Non-Disturbance: To protect yourself, you need a Non-Disturbance Agreement from the lender. This agreement states that if the lender forecloses, they will not disturb your tenancy (i.e., they will honor your lease) as long as you are not in default.

- Attornment: You agree that if foreclosure occurs, you will recognize the lender (or new owner) as your new landlord.

- Requirement: Insist that the lease requires the landlord to obtain an SNDA agreement from their current (and future) lenders for your benefit. Without it, your tenancy is at risk if the landlord has financial trouble.

Additional Important Clauses to Review:

- Signage: Rules regarding the size, location, design, installation, and maintenance of your business signs (both exterior and interior).

- Compliance with Laws: Which party is responsible for ensuring the premises comply with all applicable laws, including the ADA? Often, the landlord is responsible for base building compliance, while the tenant is responsible for compliance related to their specific use and alterations.

- Environmental Clauses: Allocation of responsibility for existing or future environmental contamination (e.g., hazardous materials). Tenants should seek indemnification from the landlord for pre-existing conditions.

- Estoppel Certificates: Requires the tenant, upon landlord request, to sign a document certifying key lease terms (rent, term, defaults) for the benefit of the landlord’s potential lenders or buyers. Ensure the lease gives you reasonable time to review and requires the certificate to be accurate.

- Holdover: Specifies the (usually significantly increased, e.g., 150-200% of normal rent) rent payable if the tenant stays in possession after the lease term expires without authorization. Negotiate for a reasonable holdover rate if possible.

- Quiet Enjoyment: A covenant ensuring the landlord will not interfere with the tenant’s peaceful possession and use of the premises.

- Rules and Regulations: Landlords often attach building rules; ensure they are reasonable and don’t unduly restrict your business operations.

The Paramount Importance of Legal Review

Given the complexity, the long-term commitment, the significant financial stakes, and the often landlord-favored nature of initial drafts, it is almost always essential for a business owner to have a commercial lease agreement reviewed by a qualified attorney specializing in commercial real estate law before signing.

An experienced attorney can:

- Identify unfavorable or ambiguous clauses.

- Explain the practical implications and risks of specific provisions.

- Advise on reasonable negotiation positions based on market standards and your leverage.

- Help draft counter-proposals or addenda.

- Ensure the lease complies with state and local laws.

- Protect your interests regarding critical issues like personal guarantees, operating expense audits, and exit strategies.

The cost of legal review is a necessary business expense that can save you exponentially more money and headaches down the road by preventing costly disputes or locking you into unfavorable terms.

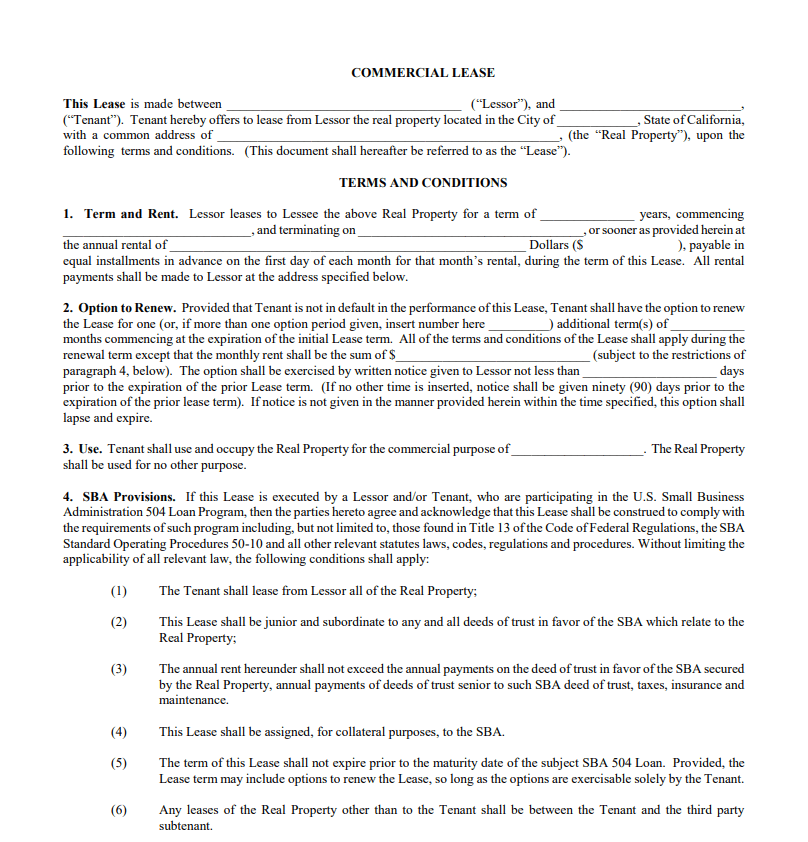

Sample Commercial Lease Agreement

Download Commercial Lease Agreement Template

Conclusion: Navigate Your Commercial Lease with Confidence

A commercial lease agreement is one of the most significant contracts your business will ever enter into. It dictates not only your occupancy costs but also impacts your operational flexibility, risk exposure, and long-term strategic options.

Approaching it with the same casualness as a residential lease is a critical mistake. By understanding the different types of commercial leases, meticulously scrutinizing key clauses – from the definition of the premises and rent structure to repair obligations, guarantees, and exit strategies – and recognizing the crucial differences from residential agreements, you empower yourself to negotiate more effectively.

Remember that the initial draft presented by the landlord is just that – a draft, designed to protect their interests. Your task is to read carefully, ask questions, identify potential pitfalls, and negotiate assertively but reasonably for terms that align with your business needs and risk tolerance. Above all, invest in professional legal counsel.

An experienced commercial real estate attorney is your most valuable ally in navigating the complexities of the lease document and securing terms that support, rather than hinder, your business’s success. Armed with knowledge and expert advice, you can move forward with confidence, transforming that potentially daunting lease document into a solid foundation for your business’s future.

References:

- What Is a Lease Agreement? A Beginner’s Guide

- Difference Between Lease and Rent Agreement: Explained

- How to Write a Residential Lease Agreement (With Template)

- How to Terminate a Lease Agreement Legally

- Understanding Security Deposits in Lease Agreements

- Month-to-Month Lease vs Fixed-Term Lease: Pros and Cons

- Tenant Rights and Responsibilities Under a Lease Agreement

- Landlord Obligations in a Lease Agreement (With Examples)

- How to Modify or Amend a Lease Agreement (Addendum Guide)